Explore a well-preserved gold mining boomtown from the 1800s.

About the Hike: This gold mining town is more than just a living museum; it's an active cultural center with art galleries, a first-rate summer music festival, and miles of hiking trails through recently-acquired parklands.

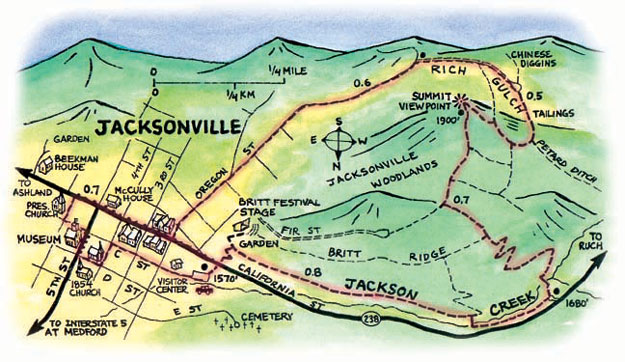

Difficulty: An easy 0.7-mile loop tours the town's streets. For a longer hike, take a 3.3-mile loop through the Jacksonville Woodlands, gaining 350 of elevation.

Season: Open all year.

Getting There: From Interstate 5, take Medford exit 30 and follow signs 7 miles to Jacksonville on Highway 238. At a "Britt Parking" sign opposite the Jacksonville Museum, turn right on C Street for four blocks to its end at a visitor center and parking lot.

Fees: None.

Hiking Tips: Start at the far end of the parking lot, where a sign announces the entrance to Jacksonville Woodlands Park. For the short loop on city streets, turn left down California Street for five blocks. A block past the clapboard 1860 McCully House, turn left at the Victorian Gothic 1881 Presbyterian Church on Sixth Street to find the 1883 county courthouse, now serving as the Jacksonville Museum-definitely worth a visit. Then zigzag to Fifth and D Streets to see two rival Protestant and Catholic churches from the 1850s before returning along C Street to your car.

If you'd like a longer hike through the woods, you'll need to start out differently. After you leave the parking lot, following a sign for Jacksonville Woodlands Park, cross the highway on a crosswalk and climb a set of stairs into the Britt Gardens. Stone walls here mark the site of the home of Peter Britt, a Swiss-born miner, painter, vintner, and photographer whose acclaimed pictures documented early Southern Oregon.

The Britt House burned in 1960. A walkway to the left leads to the amphitheater where the Britt Festival's open-air concerts are held on summer evenings. For the loop hike, however, turn right instead, following a pointer for the Sara Zigler Interpretive Trail. After just 150 feet you'll pass a 4-foot-diameter sequoia planted by Peter Britt in 1862 on the day his son Emil was born. Then the path enters a forest of Douglas fir, madrone, white oak, and ponderosa pine.

After half a mile, turn right across a footbridge over Jackson Creek, continue upstream to a parking area, and turn left across another footbridge. Then follow signs for "Rich Gulch" and "Panoramic Viewpoint," taking two right turns and two lefts, to find a knolltop bench overlooking the town and Mt. McLoughlin.

After half a mile, turn right across a footbridge over Jackson Creek, continue upstream to a parking area, and turn left across another footbridge. Then follow signs for "Rich Gulch" and "Panoramic Viewpoint," taking two right turns and two lefts, to find a knolltop bench overlooking the town and Mt. McLoughlin.

After admiring the view, continue 100 yards to a trail junction, turn right, and then keep left at all junctions to descend through Rich Gulch. Trailside signs describe the flumes and giant hydraulic hoses that washed gold from this valley, leaving cobble tailings.

When you reach paved Oregon Street, turn left for 0.6 mile to the town's historic center. If you're ready for coffee, you might stop at the Good Bean Coffee Company, on the right just before California Street. If you'd prefer nachos and local microbrews, look on the far side of California Street for the restored 1856 Bella Union Saloon. Then turn left to your car, or turn right for the loop through downtown streets described above.

History: Miners on their way to California's more famous Gold Rush discovered gold here in Rich Gulch in 1852. The tent-and-plank town that sprang up was briefly Oregon's largest. After the easy gold was panned out, giant hydraulic hoses washed away acres of land in search of gold dust. Some locals later planted fruit orchards.

When the new railroad line through Southern Oregon bypassed Jacksonville in favor of Medford in 1886, however, the city slipped into a kind of suspended animation, lacking the money to build or even to tear down buildings. The entire city was declared a historic landmark in the 1960s, and restoration began.

Geology: Jacksonville's gold didn't come from the local rock. It had washed down here from the Siskiyou Mountains long ago, and had been deposited in old river gravels. Once these old riverbeds had been washed loose and sorted out by hydraulic miners, the gold was gone.

By William Sullivan